SPOTLIGHTED PODCAST ALERT (YOUR ARTICLE BEGINS A FEW INCHES DOWN)...

Rather than jumping on the MJF-Juice Robinson feud, which I feel has been handled with far better nuance and aplomb on the “Everything with Rich & Wade” podcast than I could have written with my words, the Tweeting and the reactions to what happened in the week since has brought up several issues.

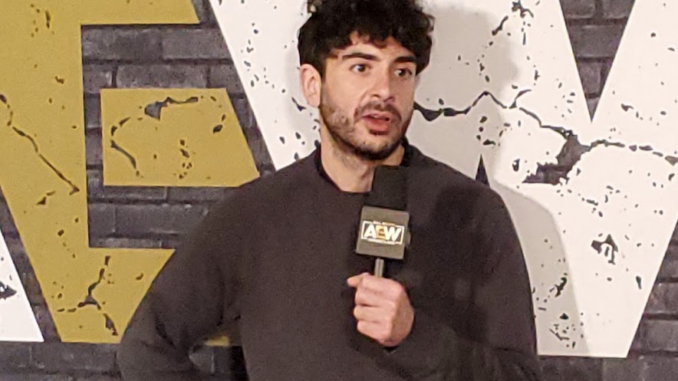

First, Tony Khan’s alignment via social media with the Warner suggestion on a book about Challenger Brands in an interview with Ariel Helwani (Oct. 5, 2022). During this interview, Tony said, “If there’s been improvement, I’m not like Burger King…”

Looking at the leader in these books, Adam Morgan’s “Eating the Big Fish” stands alone, and in my opinion most likely aligns with Tony’s behaviors since this interview. Let’s take a look tenet by tenet and see how helpful (or hurtful) this advice has been.

Looking at the leader in these books, Adam Morgan’s “Eating the Big Fish” stands alone, and in my opinion most likely aligns with Tony’s behaviors since this interview. Let’s take a look tenet by tenet and see how helpful (or hurtful) this advice has been.

Intelligent Naivety

“Intelligent Naivety enables us to ask those simple upstream questions that, as we become more steeped in the category, we lose the ability to ask: ‘Why does this category have to be all about this? Why can’t it be about that instead?'”

For this first tenet, Morgan brings up Costco, which started as just another warehouse store, then added the feature of “treasure hunts” – big screen televisions in the front of the store next to things like peanut butter, both at cheap prices for a limited time. For AEW and Tony Khan, part of this was the question of “can you feature stars that haven’t been on WWE television and sell them as stars.” The answer was a resounding yes.

Additionally, there was the question of seeking to tell stories in ring more so (at first in AEW) than just the overall focus of a feud; again, that differentiation was helpful in the opening years.

Lighthouse Identity

“Challenger Brands do not attempt to navigate by the consumer. Instead, they invite the consumer to navigate by them.”

For this, a Challenger Brand is also tasked with four additional elements, of which AEW has achieved results.

First, a point of view: “Unique view of the world based on a belief or value system.” In the book, Target and Diesel jeans were cited as good challengers that created a system, stuck to it, and let the consumer join them on the journey.

AEW has done similarly with their decision to “change the world” through professional wrestling as espoused by Kenny Omega. This has, at times, allowed the fandom to identify, defend (who can forget “yo Cleaner, I got this” guy), and spread the word of the company.

The next element, “intensity,” is described this way: “They need a wholly stronger and more emotional relationship with the consumer.” Khan, in particular, has been from day one a strong proponent of this element, with the public ban on Twitter of the Bollea family from AEW events, to shots at WWE, to even comments aimed at fans being flippant and rude. This led to cheers from the true believers.

This also dovetails into the third element of the Lighthouse identity: “Being salient/intrusive by nature.” Just coming into the scene against a dominant brand forces you to have to be the cannonball in the pool, and AEW has done a remarkable job of doing so.

Finally, being built on a rock is essential. In industry, the Mac cosmetics line was cited in the book as having been built on the Toronto drag scene. For AEW, Warner Brothers being such a strong, supportive partner gave them the legitimacy and focus groups that ECW and Impact didn’t have coming in as foundational as the largess of the Khan family and the media ties due to their NFL and Premier League involvement.

Become a Thought Leader

“There are two kinds of brand leader in any category: the Market Leader and the Thought Leader. While the Market Leader is of course one kind of brand leader in the sense that it has the dominant share and the distribution, the Thought Leader is the brand in the category that everyone is talking about, that is seen to be setting or resetting the agenda in the category.”

Of the six aspects mentioned in “thought leaders” as ways to enact this plan, “Relationship” is the biggest to me for AEW. “[Thought Leaders] can… by removing one or more of those barriers thereby [open] an entirely new kind of relationship with their consumer.”

Think about how fundamentally different AEW media calls and post-show Q&A’s were when they started, prior to the NXT/WWE doing the same, or even how AEW reacts to fan or media reactions.

Not only would you get people that were in established wrestling media, but you’d also have on those calls people from non-traditionally aligned media outlets, who in turn would report and participate and live tweet to their audiences, and fans who may not have had an interest in such a straightforward part of covering any part of sports or entertainment.

As a result, like the direct to consumer attitude – which the Bucks, in particular, mastered in the independent scene – there was a connection and relationship with the fanbase that WWE did not have. When WWE followed suit and did similar during the “Wednesday Night Wars” days, there was a different level of reaction, due to the fact that Paul Levesque would have to watch his words, given that in one breath NXT was seen as a third brand, while his boss/father-in-law would declare it merely developmental.

Create Symbols of Re-Evaluation

“It is said that a moon rocket uses half of its entire fuel supply to leave the earth and reach its desired speed. The same is true of getting a brand off the ground – the real effort and difficulty lies in achieving that initial critical momentum.”

In the book, an example is made of the Audi $120,000 car that forced re-appraisal of what it meant to have a luxury car during the Superbowl. Instead of a sports car, star ratings have been the line of demarcation for this section.

A North American-based wrestling company that is competitive with WWE is one thing; one that is killing the WWE “Developmental” is another; but to accomplish those while getting either high star ratings or seen in the aggregate via sites such as Grappl or Cagematch is rarefied wrestling air.

The triad created a nice counter base for a company competing with a billion dollar monster – where WWE will win in the boardroom with their gargantuan TV deals, AEW won “the people.”

When there’s arguments about a demographic or a television ratings subplot, the ability to cite events such as All In and its importance in wrestling history from an attendance standpoint shines a light on AEW that WWE cannot dwarf.

Sacrifice

“Challengers have to be single-minded, even if it means sacrificing what might seem to be important markets or messages.”

In the book, the big example was of Kodak in the 2000s targeting moms instead of its breadth of camera empire, which then gave them a specific focus in the decades to come.

Morgan’s point in this section hinged on the idea that “[sacrifice] also enables strong points of difference to be created by focusing on a narrow, intense loyalty rather than a weak, universal appeal.”

AEW, instead of seeking out that “next million viewers,” has at times created that intense base at the sake of the “plastics” that they may see some WWE fans as. As a result, when you think of the little “t” tribalism that erupts in any aspect of any fandom, that’s why it gets so weird when you see the lines drawn online, or in conversations off of it.

I remember walking to the first AEW show in Pittsburgh, and how different the energy of the fanbase was compared to WWE shows I’d seen for years in the past. The biggest difference was the lack of “hate attendance” – that is to say, people going because they wanted to be the show, to heckle, to absolutely derail the experience.

For WWE, as the big dog in the yard, that was to be expected – with the exception of NXT, which prior to AEW was seen as the counterculture rebel within the corporate machine. For Tony, the short term lack of growth may be a conscious sacrifice in order to create fierce loyalty, which could in turn make it an easier sell to new people later. I remain unconvinced.

Overcommit

For this chapter, the focus was going beyond where you think you’d normally go to prove something to potential customers. A liquor company named 42BELOW was the example here, whose street team showed up in winter in NYC at clubs and shoveled their walks for free. When the street team members asked about stocking their product, recognition of the prior good deeds were remembered and what should have been a super-competitive market was theirs to take.

AEW’s lived the over-commitment game via their loyalty to wrestlers’ contracts during COVID-19, vowing to refuse to take Saudi money, and consistently positing Tony’s gaffes in social media with Vince McMahon’s alleged felonious and ill-received practices.

Hammering home “we won’t do it their way even at my expense” is another rallying cry and point of pride for the AEW fanbase. However, removing the potential ability for Tony Khan to look inward when there are opportunities for growth can lead to issues (such as the Juice-MJF angle initially sparked by antisemitic prods by the heel) that then get blown up. Having fans bemoan arguing with a CEO of a wrestling company in their DMs publicly is another “eye of the beholder” scenario.

Enter Social Culture

“And we need to think about how we… ensure that we are the constant manufacturers of such social salience and mythology.”

The example in this chapter was Lexus changing the concrete floor of one of its first customers when there was an issue of an oil leak with a new vehicle at the dealer’s expense. For AEW, this has been the embedding of fan easter eggs (such as the Final Fantasy III > X), or tweets such as Tony Khan’s pre-show movie/television tie ins to his shows, or Khan’s ability to lean into social media zeitgeist.

Khan going the extra mile to shut down trolls on Twitter, or even the aforementioned DMs to fans, may be frustrating when people cover the company, but to the base that’s a guy that’s locked in and defending his people and his squad.

Become ideas centered, not consumer centered

“The reason that most Challengers lose momentum after initial success is that they fail to realize they have to change to stay the same. Changing in this sense doesn’t mean changing their core identity, but rather changing the way the consumer experiences it.”

This chapter is where I believe the biggest issue has emerged between the Khan of five years ago and the Khan of today. A lot of what we’re discussing with AEW focuses on behaviors that have persisted, rather than evolved.

While these prior moves and methods have established a second brand in nationally televised wrestling here, the customers of today and the future need to experience that a bit differently than the people that came along initially.

Constant reinvention and innovation inside and out (The Pirate Inside, Morgan’s follow up, helps with internal machinations in this regard) allows for the brand to flourish, not just a company.

Ultimately, Tony Khan and AEW are in a great place, due to Khan’s creativity, base, wrestling acumen, and memory. Khan’s willingness to push boundaries got him to where they are. Where they go from here will be determined by how that evolution continues.

(Rich Fann is a Pro Wrestling Torch columnist. He’s been contributing to PWTorch.com and PWTorch podcasts for years. He is part of the VIP-exclusive podcast series, “Everything with Rich & Wade” and also the “VIP East Coast Coast.” Paper copy subscribers of Pro Wrestling Torch can subscribe to PWTorch VIP benefits at www.pwtorch.com/govip to receive online access to over 1,700 back issues of the Pro Wrestling Torch Newsletter in PDF and text formats, 20 yearrs of podcasts, hundreds of 1990s wrestling radio shows, ad-free access to our pwtorchvip.com website, and access to daily VIP exclusive podcasts compatible with Apple Podcasts and most other podcast phone apps.) ###

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.